I love this article about teaching ancient slavery in the South by professor Sam Flores at the College of Charleston. Living in Georgia, I always bring up slavery in my tours at the Carlos Museum and when I make presentations at schools. Why? Because I think it’s important to discuss two points:

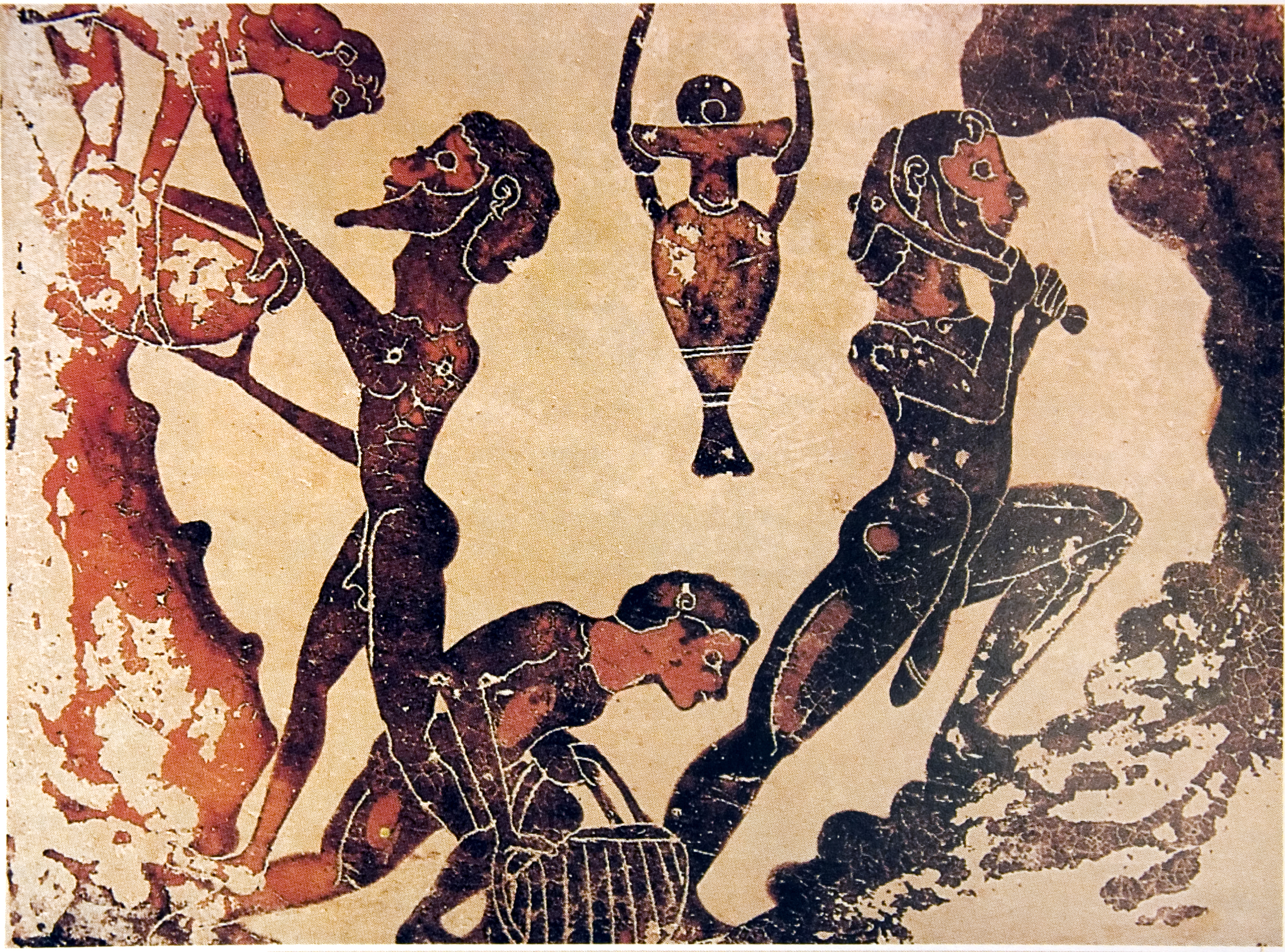

1) That most ancient slaves were not from Africa. Especially in the American South, the default face of slavery is black. There’s a psychological price, I think, for children to only ever see African faces as slaves in history. The Atlantic slave trade–especially the horrors of the American chattel-slavery system–took place more than 1,500 years after the classical world. The face of slavery in the ancient world was not African but largely Greek and Roman (i.e., European). Slaves were most often taken from defeated people in war and for the most part, the Greeks and Romans fought their neighbors (until Rome began to take over the world, but even then, the faces of slavery were still mostly European–from Italy, Greece, France, Germany, Bulgaria, Spain, and Britain).

North African, Egyptian, and middle eastern slaves, were added to the slavery pool as Rome expanded, of course, but still, Rome never succeeded in going deeper into Africa than Egypt. In my next kid’s book, I have a chapter on a kick-ass Nubian queen named Amanirenas, who personally led her armies to repel Roman forces venturing into her territories five different times, until finally, Augustus made an agreement with her to never again try invade her kingdom (Source: Strabo, 54). During most of the ancient world, Nubia–also called Kush or Meroe–was strong, powerful, wealthy, and independent. Nubia essentially controlled the ancient world’s supply of gold, iron, spices, and African wildlife.

I very much want all Southern students who are normally only exposed to one snapshot of African history to see the larger heritage of ancient African societies.

2. The other point about ancient slavery that I want kids to understand is that owning another human–a practice rightfully considered atrocious, immoral, and inhumane in our time–was considered “normal” and “inevitable” to the ancients. In other words, the ancient Greeks and Romans didn’t think that there was anything fundamentally or morally wrong with slavery AS A PRACTICE. Therefore, there were no abolition movements. Even when slaves rebelled, they weren’t trying to bring down the institution of slavery, of owning other humans–they just (!) wanted their freedom and to go home again. Indeed, Spartacus’s rebellion wasn’t about ending slavery, but began as a quest for him to return to Thrace (southeastern Bulgaria).

I like to make this point because it allows us to explore the concept that IDEAS evolve too. There was a time when almost all kings in the ancient world claimed divinity (including the Caesars) and this was considered normal. Today we scoff at that idea. There was also a time in the ancient world when slavery was considered morally acceptable and inevitable. Today, most people cannot conceive of the practice as anything beyond abhorrent and morally reprehensible.

What, I like to ask kids, do we today accept as completely “normal” and “inevitable” that a thousand years from now may leave observes scratching their heads in dismay? For me, it’s a hopeful discussion, as it reminds us that despite mankind’s universal fear of change, our ideas can evolve for the better.

Dr. Flores sums up the importance of engaging with the ugly side of the classical world up perfectly: “The reality of slavery has been one of unimaginable suffering and inhumanity for thousands of years. Its roots in classical civilization and culture serve as a reminder that we don’t study the classics solely to celebrate the achievements of antiquity, but also to understand the ways in which the culture and institutions of the ancient Mediterranean have been used and abused as exemplars to abhorrently long-lasting effect.” You can read his article here.

Leave a Reply